In service

July 2, 1942 Fort Bragg

Twin brothers Edward R. Norton and James A. Norton Jr. were obsessed with flying. After two years of study they signed up as volunteers in the US Air Force. They were trained as bomber pilots.

Twin brothers Edward R. Norton and James A. Norton Jr. were obsessed with flying. After two years of study they signed up as volunteers in the US Air Force. They were trained as bomber pilots.

Read the full story at Resources >

Stationed in England

Dec 1942, Bury St. Edmunds

In December 1942 and after their Flight Training Edward and James were sent to England and assigned to the 452nd Bombardment Squadron. At full strength their B-26 Bomb Squadron consisted of 16 aircraft and 377 men.

In December 1942 and after their Flight Training Edward and James were sent to England and assigned to the 452nd Bombardment Squadron. At full strength their B-26 Bomb Squadron consisted of 16 aircraft and 377 men.

See Edward & James' Combat route Map 1>

The second mission

May 17, 1943, North Sea

On May 17, 1943 the Norton brothers flew their first mission in a convoy of 11 Martin

B-26 Marauder bombers. Targets: the power stations of Velsen and Haarlem. The mission ended in tragedy. All the bombers were shot down.

On May 17, 1943 the Norton brothers flew their first mission in a convoy of 11 Martin

B-26 Marauder bombers. Targets: the power stations of Velsen and Haarlem. The mission ended in tragedy. All the bombers were shot down.

See Edward & James' Combat Route Map 2>

Body washed ashore

July 26, 1943 Haarlem

In September 1945 - more than two years after the disaster - Mr. Norton heard from the Mayor of Haarlem that James' body had been washed up on the beach on 26 July. Edward's body was never recovered.

In September 1945 - more than two years after the disaster - Mr. Norton heard from the Mayor of Haarlem that James' body had been washed up on the beach on 26 July. Edward's body was never recovered.

See Edward & James' Combat route Map 3>

Final resting place

after the war, Margraten

After the war, the Norton family decided that Edward & James should find their final resting place in Margraten. Of the crew members killed on 17 May 1943, twelve are buried in Margraten, including James (P-16-5). Edward's name can be seen on the Walls of the Missing along with the names of seven other crew members.

See Edward & James' Combat route map 4>

July 1943 (?)

Registration ARC

September 1943

to the UK

July 16, 1944

Landing on Utah Beach

March 15, 1945

Siegfriedlinie

May 1, 1945

Died on pleasure flight

June 19, 1945

Buried in Margraten, Block RR, Row 12 Grave 290

February 18, 1943

Air Evac. Nurse diploma

Jan. 15, 1944

Married

July 26, 1943

Body washed up

March - Augus 1943

Panama

June 1944

To Europa

November 23, 1943

Departure for Europa

January 20, 1944

Arriving in England

June 1944

Landing Omaha Beach

US enters the war

December 11, 1941

Nazi Germany declares war on the US

Turnaround WWII

Februari 2, 1943

Battle of Stalingrad: Red Army defeats Germans

The Norton twins

Born aviators

| Born: | Augustus 18, 1920 |

| Location: | Conway, Horry County, South Carolina |

| Family: |

|

| Education & profession: | In 1938 started a study in Civil Engineering at Clemson University, but decided to stop their studies and to enlist in the Army Air Corps as Aviation Cadets. |

| Military career |

|

| Burial History: |

|

Norton twins - born aviators

Edward R. Norton and James A. Norton Jr. were destined to become pilots. During their childhood they were interested in planes and wanted nothing more than to become pilots. When the war broke they enlisted in the US Army Air Force (USAAF) a logical step.

But along with many pilots they did not survive the war.

On May 17, 1943 they conducted their first mission over the

Netherlands: bombing the power plant in Velsen. Tragically,

their aircraft was shot down during their first mission. James A. Norton Jr. was buried

in Margraten. Edwards body was never found, his name is engraved on the Walls of the

Missing. Both brothers were only 22 years old.

They grew up in Conway in Conway, South Carolina

Edward Robertson Norton & James Arthur Norton Jr. was born on August 18, 1920. Their parents were Arthur James Norton (1876-1950) and mother Eddie Robertson (1883-1955). The family consisted of five children: Eugenia / Jane (1906-), Jamie (1912-), Evan (1917) and Edward R. & A. James Jr. (Both August 18 1920). Two daughters died at a very young age.

The Norton family lived in Main Street in the village of Conway in Horry County, South Carolina. Father James Norton was a doctor, their mother - Miss Ed - was well-known for her work in the local church and her love of music and art, and also for the way she brought up the children.

James Arthur Junior was named after his father Arthur and was nicknamed 'Wack'. Edward Robertson was named after his mother and was nicknamed 'Hogie.

Budding aviators

The brothers were fascinated by flying and airplanes from an early age. They built model airplanes and flew them. At the age of 14, when they went to Conway High School their parents bought them a second hand plane.

Father Norton even bought a piece of land where they could build a runway.

When Edward and Arthur had finished high school at the age of 18 they had both already made about 50 flight hours. They traded their old aircraft for a new airplane.

After graduating from high school in 1938 they went to Clemson University to pursue studies in Civil Engineering. They excelled in football and athletics, especially the high jump.

In service with the Air Force

After two years of college the twins decided to give up their studies and to volunteer for the US Air Force. The twins probably indicated that they wanted to stay together. Volunteers were able to stay with their siblings; draftees were not given this choice.

They began their training as Aviation Cadets in Arcadia, Florida. After this, they went to Carlstrom Airfield to follow Primary Pilot Training. Then they went to the Basic Pilot Training School in Greenville, Mississippi. After having successfully completing the training, they started the final part of their training: the Advanced Flying School in Columbus Army Flying School, Alabama. They were promoted to officers on 2 July 1942 and on September 6 they received their 'wings' (paratroopers license) and they were installed as officers in the (starting) rank of 2nd Lieutenant.

After obtaining their license, the brothers were assigned to

the 322 Bombardment Group which was set up on June 19

1942 and activated on July 17, 1942. This Bombardment Group

flew Martin B-26 Marauder bombers. As of July 1942 there were four months of hard practice with the B-26's before they were ready for battle.

The Martin B-26 Marauder

The Martin B-26 Marauder bomber (from here: B-26) was a twin-engine bomber, which was built by the Glenn L. Martin Company (hence Martin B-26 Marauder). All aircraft that came from the factory had names that start with an 'M': Martin 167 Maryland, Martin AM Mauler, Martin P4M Mercator and the Martin B-26 Marauder.

The B-26 was deployed in combat operations from the beginning of 1942. The first mission in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) was on May 14, 1943, of which more later.

A B-26 was staffed by seven people: a pilot, copilot, navigator, radio operator, a mid gunner, flight engineer and tail gunner. The pilot, copilot, navigator, radio operator and mid gunner were officers; the flight engineer and tail gunners were NCOs.

A B-26 could carry up to 2,600 kg of bombs, although that was not usually the case due to the limited flying range. The space in the rear was mostly used to carry an extra fuel tank.

A B-26 was nearly 18 meters long and 6.5 meters in height and

weighed 11.000 kg (dry weight). The maximum speed was

460 km p/h at 1,500 meters and the cruising speed was

358 km p/u. During missions it had a maximum flight range of 1,850 km.

The Widowmaker

The first flights made in the B-26 were not always successful and there were some fatal accidents. No test fights were made and the B-26 soon acquired the nickname of The Widowmaker.

This was not surprising, as the contract for the design of the aircraft was made in 1939 and the first aircraft was commissioned and delivered to the military in 1940. So there was in fact no prototype or test phase. Pilots in the US Air Force had to immedidately work with the plane to figure out by trial and error the best way to fly the aircraft.

The B-26 quickly proved no plane for beginners, which was problematic as many of the new pilots were fresh from the Flight Academy. One of the things that went wrong in the beginning was that the plane maintained a high speed during landing. For many pilots it was frightening and counter-intuitive and also contrary to what was in the manual.

Gradually they learned how it could best be flown. Despite the bad start, at the end of the war, the B-26 had suffered the fewest losses. However, this was not the case in May 1942 when preparations were made to deploy.

In Europe

Back to the brothers After completing their Flight Training

the 322 Bombardment Group was transferred

to England in December 1942. The base was USAAF Station 468, Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.

The brothers were assigned to the 452 Bombardment Squadron. At full strength B-26 Bomb Squadron consisted of 16 aircraft and 377 men (67 officers and 310 NCOs and men).

The 322 Bombardment Group consisted of four Bomb Squadrons: 449, 450, 451 and 452 BS and a headquarters (HQ). Total Group was - again at full strength - 1591 men plus 64 aircraft.

While the men arrived in England in December, it took until March 1943 for all the aircraft to arrive. Further exercises were immediately started. That turned out to be very necessary: the most recently graduated airmen appeared to have little experience with formation flying and some of the gunners had never shot with a machine gun during a flight!

The goal of the commanders was for the B-26 to fly at zero altitude - just above the ground. An additional problem: none of the pilots at that time had ever flown at below 1000 feet - 300 meters.

So flying low was extremely dangerous, especially with the B-26 which ws slow to respond to changes in altitude. On April 26 it went very wrong when the entire crew of an aircraft was killed during a training flight.

Bombings and human rights

Why were the B-26s flying so low when it was so dangerous?

The answer is not military but political:

when a bomber flies low, bombs can be dropped more accurately. This significantly reduces the risk of civilian casualties. The higher a bomber flies, the greater the probability that the bombs would fall on civilian targets; especially in the densely populated areas of northwestern Europe. In 1943 significant political pressure was exerted on the military leadership to make sure the B-26 flew as low as possible..

A second advantage - this time of a military nature - was that when the aircraft flew low, it could not be detected by the German radar. The military leadership thought that the B-26 in Europe would have the same success as in the Pacific. The reality would quickly turn out differently, because German Flak was of very different quality than that of the Japanese.

Mar 14, 1943: the first mission

Approximately two months after the B-26s had arrived at the base in Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, the 322 Bombardment Group was fully operational and ready to fly its first mission, which took place on May 14, 1943. Although the Norton brothers were not part of this mission, they will undoubtedly have followed the mission from minute to minute

The target was a power plant in Velsen, which supplied power to blast-furnaces in IJmuiden, a bunker holding German submarines and the rail network between Amsterdam and Rotterdam. All these were very important for the Germans.

The mission that day was carried out by 12 B-26's.

All the aircraft were equipped with four bombs of 500 pound,

or about 225 kilograms. Such a bomb had a kill zone

of 400 meters and a blast zone of up to 800 meters. The bomb could therefore cause damage over 800 meters.

There was no support available, but there were at the same time 8 B-17 and B-24 operating in the same area who were supported by fighter aircraft and thus could provide diversions.

The planes took off at 10 in the morning, and reached a height of about 75 meters. Once above water, they dropped to 15 meters. They arrived at exactly the right spot to land in the Netherlands over a hotel along the beach in Noordwijk. At that time the B-26's were under fire from German flak.

The pilots tried to avoid the air defenses as much as possible and eventually only one plane was hit and had to return to England. The onward flight to Velsen went smoothly. At the moment the North Sea canal came into view - the target - the German Flak started again. The B-26's climbed to 75 meters and dropped their bombs.

Suddenly, Scott's aircraft was hit by 20 mm Flak. The grenade hit the cockpit injuring Captain Scott in the face. Scott later remembered it this way: "I thought my face was blown away, but I could just see enough with one eye to keep the aircraft under control. We hit the ground but we could not get the aircraft back under control. Later, I had to lie down in order not to become unconscious and not to put the whole crew and aircraft at risk.

Several aircraft were severely damaged by

FLAK, but none was shot down.

Within a short time the aircraft were near the coast and could begin the

return trip. One of the aircraft was so badly damaged that the landing gear did not deploy. After several attempts, it was decided to abandon the plane and jump out. All the crew members left the aircraft and opened their parachutes. Only the pilot, Lieutenant Howell, was not able to get out in time.The plane then crashed. Of the 12 crew members that day he was the only who did not survive.

The mission seemed to have been unsuccessful

During the debriefing the crew were informed that the anti-aircraft fire had been more intense than they thought. However, they had dropped all their bombs on the target.The reconnaissance by the RAF the day after was eagerly awaited.

The findings that the RAF presented two days later were much less rosy. The bombing had not been a success. The big question was why not? Had the Germans managed to defuse the bombs in time or had they removed them in time? By agreement with the Dutch government the bombs had a 30 minute delay, which gave the Dutch workers time to get out before the bombs went off. This delay, however, gave the Germans the chance to render the bombs harmless.

The target

Why target the power station at Velsen ? The answer is

in the strategy of the US Army, which wanted

to frustrate and disrupt the German war industry as much as possible. To achieve this it was decided that the Air Force would focus on three main objectives:

|

Seen from that perspective, the power plant in Velsen was a logical target. This power station in IJmuiden included blast furnaces which provided power for the rail network between Amsterdam and Rotterdam. It also provided power for the nearby German submarine bunker.

The Germans were naturally well aware of the fact that the US and British air forces would try to bomb such strategic goals. So a considerable number of anti-aircraft guns were placed near these important targets to defend them against Allied bombing missions.

Mat 17, 1943: second mission

After the reconnaisance flight had showed that the first attack

had not been a success, the military command decided

to immediately carry out a new attack.

Brigadier General Brady, commander of the 3rd Bombardment Wing, of which 322 Bombardment Group was part, gave Lieutenant Colonel Stillman, commander of 322 BG, the order to fly the mission. Stillman was stunned when he heard the order. A new attempt, three days after the first attempt, would be nothing short of a suicide mission. The Germans would be extra wary after the first attack, especially since the bombing of May 14 had failed.

Stillman raised his objections to Brady: "Sir, I will not send them out." After a silence, Brady replied: "You will, or the next commander will". Stillman had no choice but to follow orders.

The plans were identical to those of May 14: 12 bombers would make for Velsen. The only difference was that some of the group would target the power station in Haarlem. Lieutenant Colonel Stillman would lead the formation and direct the bombing of Velsen, Lt. Col. Purinton had command of the bombing of Haarlem. No escort of fighter pilots was dispatched, despite repeated requests, including one from Major Alfred von Kolnitz.

Although the crew of the B-26's had confidence in their ,

abilities, there were many who thought that they would not

come back this time. On the morning of May 17 there were

only 11 operational bombers. The attack on May 17, 1943 was the first mission for Edward and James. With the other crews they took off just beore 11.00 a.m. The flight to the Dutch coast took about half an hour.

The Norton crew consisted of seven people: 2nd Lt. Edward Norton was 1st pilot, 2nd Lt. James Norton was co-pilot, Lieutenant Alvin Zeidenfeld was navigator and mid gunner, Staff Sergeant Ralph MacDougall was flight engineer and gunner, Staff Sergeant Harrison Kegg operated the radio and Sergeant Bennett Longworth was tail gunner.

Just as three days earlier the B-26's first climbed to 75 meters height above the sea, then flying lower to 15 meters. One of the aircraft experienced technical difficulties near the Dutch coast and had to turn back. As there was no procedure for the change of plan of the mission, the crew decided to turn 180 degrees and to climb up to 300 meters.That proved to be a disastrous decision, because suddenly the Germans located the aircraft on their radar and alerted the German coast guard. The Germans may have been alerted to the aircraft by the the powerful receivers positioned on the Dutch coast.

As several enemy vessels had been observed, Stillman decided to veer slightly to the south in order to hopefulyl confuse the Germans. He thought he was flying about 10 km south of the original landing point of Noordwijk, but he was mistaken. The formation was much further south, at the Hoek van Holland. The Festung Hoek van

Holland, along with Festung IJmuiden, was one of the best

defended parts of the Dutch coast...

Both defenses were part of the Atlantikwall: a 2685 km long

coastal defense built by the Germans from Lapland to the South

of France.

From the moment they were over land, the Germans fired. Stillman's plane was hit almost immediately and crashed. (11:51). Miraculously Stillman and three of his crew survived the crash, although they would spend the rest of the war in captivity. Stillman would recall later: "The plane rolled like a corkscrew. I was not scared, I had no time to fear. A wing pointed down, I looked out the window and saw the ground coming at us. There was nothing to do, I closed my eyes and waited. The strange thing is that you do not worry at a time like this ... ".

A few kilometers further Lieutenant Garrambone's plane was hit and crashed in the Meuse (11:52). Lieutenant Wolf was now in command, but in attempting to dodge the Flak he hit Lieutenant Wolf's aircraft. Both planes crashed near Bodegraven (11:58). Only two gunners survived the crashes.

Lieutenant Wurst, who was flying right behind the planes, could not avoid the wreckage and made a belly landing near Meije (11:58). His entire crew survived.

From the 10 B-26s there were now only five and they were

nowhere near the target. What was worse was that no one

knew exactly where they were. They looked out for landmarks

in the landscape, but couldn't recognize any. Just as Lt. Col. Purinton, now commander, was planning to abandon the mission, his navigator thought he could spot the target. The bomb doors were opened and the plane flew toward what they thought was the Haarlem power station, but which in reality was a gas tank of South Gasworks west of Amsterdam. The other planes also targeted the gas tank, but without success.

What the crews did not realise was that they were flying directly towards their target: the heavily defended port of IJmuiden. Again they came under fire from 20 mm Flak. This time the plane which the Norton brothers, were flying, as well as the aircraft of Lt. Col. Purinton and Lieutenant Jones were hit. All three aircraft crashed just off the coast of IJmuiden into the North Sea (12:12 & 12:13). Edward and James did not survive. Both brothers died as they had lived: inseparable. Tail Gunner Longworth was the only survivor from the Norton brothers' plane. He spent the rest of the war in captivity.

The last two remaining aircraft were flown by Captain Crane and Lieutenant Matthew. They started to fly back to England, but they would not make it. After about 80 kilometers the two aircraft were attacked by two German Focke-Wulf 190 fighters. The B-26's did not stand a chance. Captain Crane's plane, which was badly damaged, was shot first and crashed into the sea (12:18). Only Sergeants Williams and Lewis were able to leave the aircraft on time and were picked up by an English warship.

Twelve minutes later, Lt. Matthew's aircraft

was also hit and crashed(12:30). No one survived...

Losses

The mission turned out to be a disaster, as many had expected. None of the 10 planes returned to England. 34 crew members were killed, 24 were taken prisoner, and only 8 ultimately returned to England.

Twelve days after that disastrous mission the 322 Bombardment Group was again struck by misfortune: one of their B-26s crashed at the airport, killing the entire crew and damaging a hangar. After all these tragedies it was decided to fly the B-26 at higher altitudes and to arm them better. This and other measures eventually led to the B-26 squadrons having the lowest losses of all US bombers. At the end of the war and after some 29,000 flights over Europe, 139 aircraft had been lost.

Unfortunately for the Norton brothers they flew in the second mission of B-26s in the ETO at a time in the war when the US Air Force was still experimenting with how to use the aircraft.

Conway mourns

Edward Robertson Norton & James Arthur Norton Jr. both died on May 17, 1943 in the chilly waters of the North Sea. They were at that time 22 years old.

Their parents received two messages on May 19.

Missing in action… All of Conway sympathized. For months

the family heard nothing more. Eventually Mr. Norton

learned that his sons' plane had crashed in the North Sea. In September 1945, more than two years after the disaster, he heard from the Mayor of Haarlem that James' body had been washed up on the beach on July 26. Edward's body was never recovered.

Conway mourned. Stories were told about the twins and retold: how the twins loved flying, how promising they were, they were always together. Both brothers were awarded posthumously a Purple Heart. Every soldier in the US Army who gets injured or dies while serving receives a military award.

After the war the Norton family decided that Edward & James would find their final resting place in Margraten. Of the crew members killed on17 May 1943, twelve are buried in Margraten and this includes James Norton (P-16-5), Alvin Zeidenfeld (R-22-17) and Ralph MacDougal (P-22-3). The names of the seven crew members are listed on the Walls of the Missing, including Edward Norton. The body of Harrison Kegg was never found; strangely his name appears on the Walls of the Missing at Cambridge American Cemetery in England.

Edward and James were commemorated in Conway by

two cenotaphs at the local Lakeside Cemetery.

Although the Norton twins died over 70 years ago, the people of Conway, South Carolina still remember the aviators.

In memory of the brothers a new terminal at the Myrtle Beach airport, just east of Conway, was named after them in 2010: Norton General Aviation Terminal. A plaque commemorates them.

Fields of Honor Database

Downloads

-

Literature

Images

|

A B-26

Source: US Air Force / Public domain |

|

drawing with the crew of a B-26

Source: USAAF / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

Close-up of B-26 ‘Fightin’ Cock’ of the 322 Bombardment Group.

Source: US Air Force / Public domain |

|

German flak: 20mm Flak Vierling 38

Source: German National Archive |

|

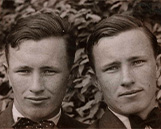

James (L) and Edward (r) in their High School year book, 1938

Source: Horry County Museum |

|

James (L) and Edward ( r) in American football uniform

Source: Clemson University / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

James (l) and Edward (r) in their High School year book, 1938

Source: Horry County Museum |

|

Conway High School

Source: Horry County Museum |

|

Mainstreet, Conway, rond 1940

Source: Horry County Museum |

|

The Freshmen of Clemson University in 1939.

Source: Clemson University / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

Logo 322nd Bombardment Group

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/322d_Air_Expeditionary_Group |

|

Aerial view of airport Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk (in 1955)

Source: United Kingdom Government / Public domain |

|

Purple Heart Medal

Source: Public domain |

|

B-26 ‘Dee-feater’

Source: US Air Force / Public domain |

|

James (l) and Edward (r) Norton

Source: Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

A handwritten letter from Arthur and Edward Norton to Nuny

Source: Horry County Museum |

|

A handwritten letter from Arthur Norton to Nuny

Source: Horry County Museum |

|

Poster US Air Force B-26

Source: US Air Force / Public domain |

|

Plaque of the terminal is named after the Norton twins.

Source: internet |

|

Lieutenant Colonel Robert W Stillman

Source: www.stillman.org |

|

Major General Robert W Stillman

Source: US Air Force |

|

A formation of B-26

Source: USAAF / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

Bombs a B-26 loaded

Source: Life Magazine |

|

Drawing Life Magazine with all components of a B-26

Source: USAAF / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

Briefing crew on May 14

Source: USAAF / Stillman / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

top left power plant

Source: USAAF / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

'Zuidergasfabriek' gasworks gas tank that was mistakenly bombed

Source: Stadsarchief Amsterdam |

|

A low-flying B-26 formation BG 386

Source: USAAF / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

Debriefing of the mission on May 17

Source: USAAF / Stillman / Public domain / Collection Arie-Jan van Hees |

|

A Focke Wulf 190

Source: USAAF / Public domain |

|

Lakeside Cemetery at Conway, South Carolina

Source: Lakeside Cemetery te Conway, South Carolina |

|

Memorial Plaque James Norton Jr.

Source: Ancestry.com / Find a grave / Chuck Mull |

|

Memorial Plaque James Norton Jr.

Source: Ancestry.com / Find a grave / Chuck Mull |